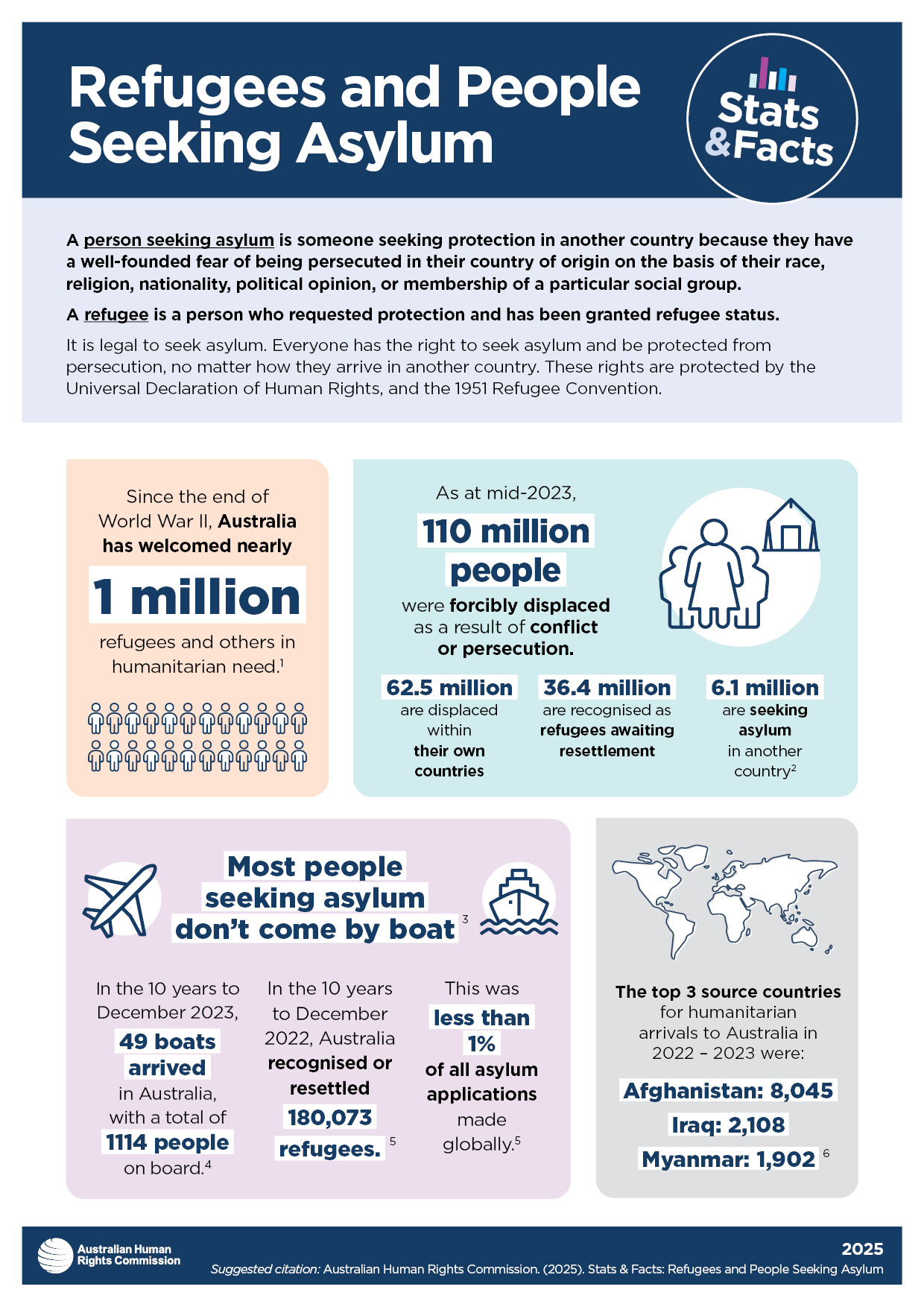

Statistics about Refugees and People Seeking Asylum

A person seeking asylum is a person seeking protection in another country because they have a well-founded fear of being persecuted in their country of origin on the basis of their race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership of a particular social group.

A refugee is a person who requested protection and has been granted refugee status.

It is legal to seek asylum. Everyone has the right to seek asylum and be protected from persecution, no matter how they arrive in another country. These rights are protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the 1951 Refugee Convention.

Demographics

- Since the end of World War II, Australia has welcomed nearly 1 million refugees and others in humanitarian need.[1]

- As at mid-2023, 110 million people were forcibly displaced as a result of conflict or persecution.

- 62.5 million are displaced within their own countries

- 36.4 million are recognised as refugees awaiting resettlement

- 6.1 million are seeking asylum in another country[2]

How people come to Australia

- In the 10 years to December 2022, Australia recognised or resettled 180,073 refugees. This was less than 1% of all asylum applications made globally.[3]

- Most people who seek asylum in Australia do not arrive by boat.[4]

- In the 10 years to December 2023, 49 boats arrived in Australia, with a total of 1114 people on board.[5]

- Between 7 September 2013 and 21 May 2022, 143,749 people arrived by plane and made an application for a permanent Protection visa in Australia.[6]

Where people are arriving from

- The top 3 source countries for humanitarian arrivals to Australia in 2022 – 2023 were:

- Afghanistan: 8,045

- Iraq: 2,108

- Myanmar: 1,902[7]

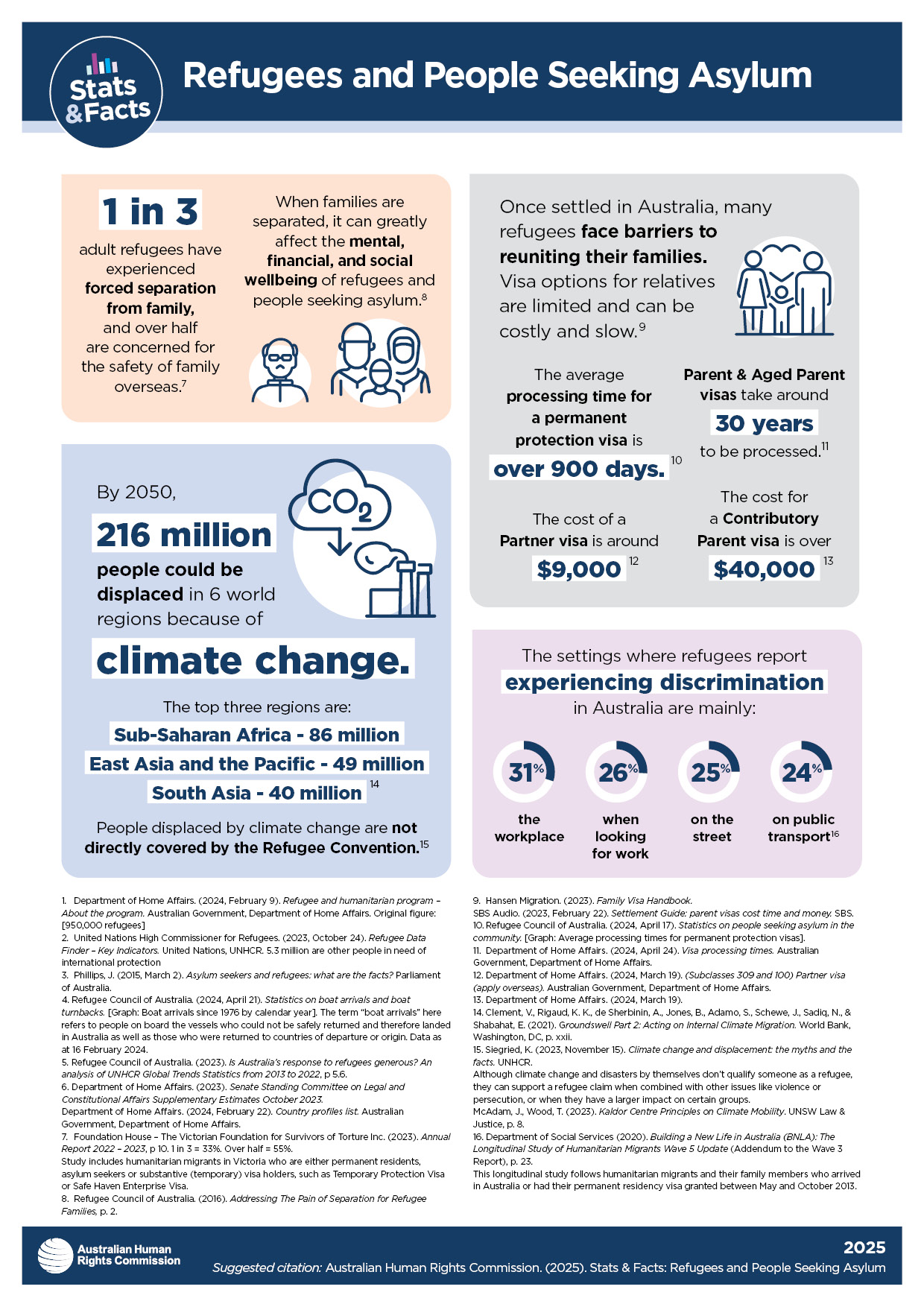

Family separation and barriers to reunification

- 1 in 3 adult refugees have experienced forced separation from family, and over half are concerned for the safety of family overseas.[8]

- When families are separated, it can greatly affect the mental, financial, and social wellbeing of refugees and asylum seekers.[9]

- Once settled in Australia, many refugees face barriers to reuniting their families. Visa options for relatives are limited and can be costly and slow.[10]

Experiences of discrimination

- The settings where refugees report experiencing discrimination in Australia are mainly:

- The workplace (31%)

- On the street (26%)

- When looking for work (25%)

- On public transport (24%)[15]

Consequences of climate change

- By 2050, 216 million people could be displaced in 6 world regions because of climate change. The top three regions are:

- Sub-Saharan Africa (86 million)

- East Asia and the Pacific (49 million)

- South Asia (40 million).[16]

- People displaced by climate change are not directly covered by the Refugee Convention.[17]

References

[1] Department of Home Affairs. (2024, February 9). Refugee and humanitarian program – About the program. Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs. Original figure: [950,000 refugees].

[2] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2023, October 24). Refugee Data Finder – Key Indicators. United Nations, UNHCR. 5.3 million are other people in need of international protection.

[3] Refugee Council of Australia. (2023). Is Australia’s response to refugees generous? An analysis of UNHCR Global Trends Statistics from 2013 to 2022, p 5.

[4] Phillips, J. (2015, March 2). Asylum seekers and refugees: what are the facts? Parliament of Australia.

[5] Refugee Council of Australia. (2024, April 21). Statistics on boat arrivals and boat turnbacks. [Graph: Boat arrivals since 1976 by calendar year]. The term "boat arrivals" here refers to people on board the vessels who could not be safely returned and therefore landed in Australia as well as those who were returned to countries of departure or origin. Data as at 16 February 2024.

[6] Department of Home Affairs. (2023). Senate standing committee on legal and constitutional affairs supplementary estimates October 2023.

[7] Department of Home Affairs. (2023). Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs Supplementary Estimates October 2023.

Department of Home Affairs. (2024, February 22). Country profiles list. Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs.

[8] Foundation House – The Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture Inc. (2023). Annual Report 2022 – 2023. p 10. 1 in 3 = 33%. Over half = 55%.

Study includes humanitarian migrants in Victoria who are either permanent residents, asylum seekers or substantive (temporary) visa holders, such as Temporary Protection Visa or Safe Haven Enterprise Visa.

[9] Refugee Council of Australia. (2016). Addressing The Pain of Separation for Refugee Families, p. 2.

Liddell, B. J., Byrow, Y., O’Donnell, M., Mau, V., Batch, N., McMahon, T., Bryant, R., & Nickerson, A. (2020). Mechanisms underlying the mental health impact of family separation on resettled refugees. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 55(7), 699-710.

[10] Hansen Migration. (2023). Family Visa Handbook.

SBS Audio. (2023, February 22). Settlement Guide: parent visas cost time and money. SBS.

[11] Department of Home Affairs. (2024, March 19). (Subclasses 309 and 100) Partner visa (apply overseas). Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs.

[12] Department of Home Affairs. (2024, March 19). (Subclasses 309 and 100) Partner visa (apply overseas). Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs.

[13] Department of Home Affairs. (2024, April 24). Visa processing times. Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs.

[14] Refugee Council of Australia. (2024, April 17). Statistics on people seeking asylum in the community. [Graph: Average processing times for permanent protection visas].

[15] Department of Social Services (2020). Building a New Life in Australia (BNLA): The Longitudinal Study of Humanitarian Migrants Wave 5 Update (Addendum to the Wave 3 Report), p. 23.

This longitudinal study follows humanitarian migrants and their family members who arrived in Australia or had their permanent residency visa granted between May and October 2013.

[16] Clement, V., Rigaud, K. K., de Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Adamo, S., Schewe, J., Sadiq, N., & Shabahat, E. (2021). Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration. World Bank, Washington, DC. p. xxii.

[17] Siegried, K. (2023, November 15). Climate change and displacement: the myths and the facts. UNHCR.

Although climate change and disasters by themselves don't qualify someone as a refugee, they can support a refugee claim when combined with other issues like violence or persecution, or when they have a larger impact on certain groups.

McAdam, J., Wood, T. (2023). Kaldor Centre Principles on Climate Mobility. UNSW Law & Justice, p. 8.

Downloads

- Refugees and People Seeking Asylum fact sheet PDF (165 KB)

- Refugees and People Seeking Asylum fact sheet Word (65 KB)

Suggested citation

Australian Human Rights Commission. (2025). Stats & Facts: Refugees and People Seeking Asylum.